Diarmaid MacCulloch, Thomas Cromwell: A Revolutionary Life, London: Penguin Random House 2018.

728 pages, hardback. 45 full-colour plates.

ISBN 9780670025572

$50 online.

The downside to studying theology at Melbourne’s Trinity College in the 1970s was the lack of explicit input concerning Anglicanism. The upside, of course, was access to the best lecturers in Australia regardless of denomination, and the cross-fertilisation between Methodists, Presbyterians, Roman Catholics and Anglicans.

We needed both, of course; the grounding in our own tradition, and tools to engage with others. Overall, Trinity didn’t do too badly, but I have felt my lack of knowledge about our Anglican tradition – until now. Reading Diarmaid MacCulloch’s Thomas Cromwell was like a semester-length course in the English Reformation with a particularly knowledgeable and clear communicator of Church History.

The first and obvious thing I learned was that the clichés of Henry VIII starting the Church of England solely to have his marriage to Queen Katherine annulled, and of Cromwell, the systematic destroyer of monasteries, are both wrong.

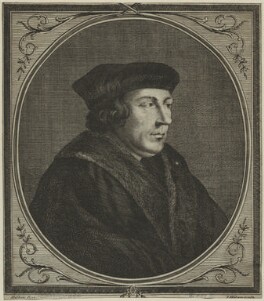

Cromwell did become one of Henry’s chief ministers, rising to Lord Privy Seal and Vice-Gerent of the Church before being torn down by enemies like the Duke of Norfolk and finally beheaded on the King’s orders. Henry and Cromwell were both politicians who needed each other, but MacCulloch discerns their subtly different agendas. Henry was at times obsessed with the Queen question, but he also sought to be the Supreme Head of a Church with the best of Lutheran theology and the conservation of many papist ideas, especially the real presence of the Lord in the bread and wine of Holy Communion.

Henry was a progressive Catholic, believing he could achieve a middle way conserving the best of Rome and political stability. Luther had given rise to great instability, so it was wisest while presenting Henry with Lutheran books, not to mention the name!

MacCulloch, who is Professor of the History of the Church at Oxford University, argues that Thomas Cromwell pursued a consistent ‘evangelical’ agenda, ‘evangelical’ being the term he chooses to describe those pressing for reform. Cromwell knew how to use the power King Henry gave him as his Vice-Gerent of the Church. He put himself above all the bishops, even above his friend Archbishop Cranmer of Canterbury. He invited scholars from Geneva to bring reformed ideas to England. He promoted his ‘evangelical’ friends to important bishoprics. He encouraged printers to produce tracts that expressed his ’evangelical’ ideas, and was not afraid to explore even more radical views.

Cromwell ’s role in the dissolution of the monasteries is dissected with clarity, explaining why Cromwell ordered some to hand over their property to the king, while remaining friends with the Abbots and Priors of others.

Following his early mentor Cardinal Wolsey, Cromwell wanted to reform monastic life. In particular, he wanted them to become centres of bible study, social justice (including proper provision for the poor) and morality. Cromwell made sure there were proper pensions or livings for the monks after the lands of their monastery were distributed to the wealthy. The Anglican Church never condemned the principle of monasticism, just its corruption.

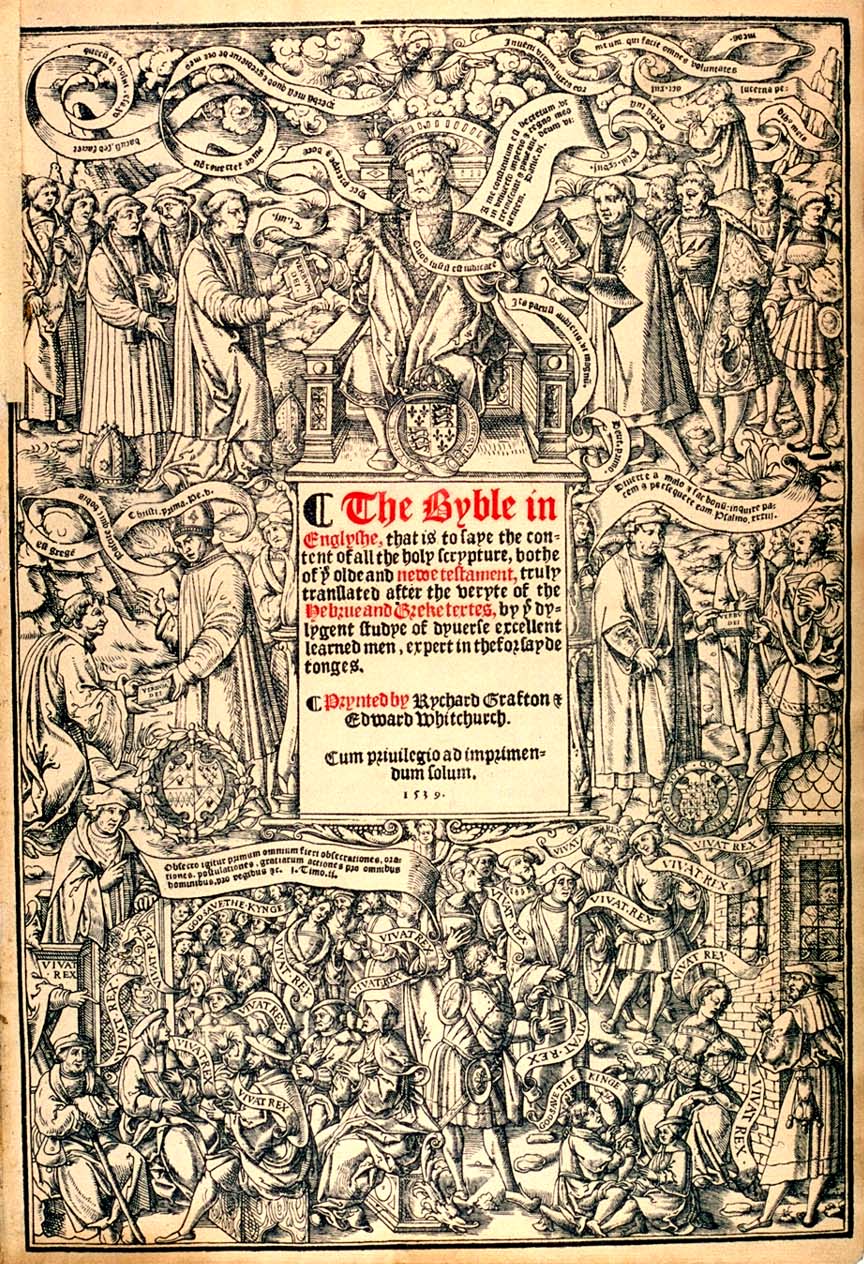

He promoted the principle of ordinary Christians reading the Bible, sometimes risking the King’s anger. He manoeuvred the King and Parliament into insisting that every church have an English Bible. Henry finally took pride in the Great Bible whose influence carried through all English translations. Cromwell often turned to the friar Miles Coverdale to carry out the work of translation.

It was the King, particularly when he needed more and more money to build up the coastal defences, who saw the dissolution of monasteries as a cash cow. He often left the details, and the blame, to his minister.

Thomas Cromwell was skilled in getting things done. He generated the contacts, he used his power ruthlessly, and he did more than others in centralising the organisation of the kingdom. He divided Wales into shires and put in charge there a trusted lieutenant. He tried the same, without great success, in Ireland.

Cromwell played a leading part in turning Tudor England from an island backwater into a major power. As a Member of Parliament responsible for managing the King ’s business first in the Commons and then in the House of Lords, Cromwell threw himself with great energy into the detail of legislation and process.

It may well be that Thomas Cromwell was the reason England did not experience the same violence as did Germany and other reforming countries.

The mystery of Thomas Cromwell is how he rose from the yeoman class to the most powerful Lord in the land after his King. Little is known of his early life, although MacCulloch has more information than other biographers. He learned several languages, presumably while in Europe. It was probably then that he developed his interest in the reform of the Church. He made friends with a number of Europeans, and used them to grow an import business. At some time, he was picked up by Cardinal Wolsey who trained him as a politician.

Professor MacCulloch traces the life of a great man whose influence in the development of England and the Anglican Church was long-lasting. Cromwell teased out the interdependence for England of Church and State. He served Henry VIII, that difficult master, with deep loyalty. He also inspired deep enmity, and conservative noble churchmen like the Duke of Norfolk were ever ready to bring down the upstart.

Though they succeeded, within a year, the King was complaining that he had lost his best advisor. Many of the men he had put into positions of power remained there after his death and extended their mentor’s influence in their lifetime.

Diarmaid MacCulloch has written a highly readable biography which should be a standard text for students of Anglicanism. For me, I am grateful that a large gap in my theological education has been filled so thoroughly and enjoyably.

I find I can read him with ease, he makes the way smooth. Enjoyed your personal reflection.