Sermon at Saint Brendan’s-by-the-Sea, Warnbro, October 8, 2023

If you would rather listen to Ted preaching this sermon, click on the audio below:

The Lord be with you.

And also with you.

The Holy Gospel according to Saint Matthew

Glory to you, Lord Jesus Christ.

(Matthew 21:33-46)

33 ‘Listen to another parable. There was a landowner who planted a vineyard, put a fence around it, dug a wine press in it, and built a watch-tower. Then he leased it to tenants and went to another country. 34 When the harvest time had come, he sent his slaves to the tenants to collect his produce. 35 But the tenants seized his slaves and beat one, killed another, and stoned another. 36 Again he sent other slaves, more than the first; and they treated them in the same way. 37 Finally he sent his son to them, saying, “They will respect my son.” 38 But when the tenants saw the son, they said to themselves, “This is the heir; come, let us kill him and get his inheritance.” 39 So they seized him, threw him out of the vineyard, and killed him. 40 Now when the owner of the vineyard comes, what will he do to those tenants?’ 41 They said to him, ‘He will put those wretches to a miserable death, and lease the vineyard to other tenants who will give him the produce at the harvest time.’

42 Jesus said to them, ‘Have you never read in the scriptures:

“The stone that the builders rejected

has become the cornerstone;[a]

this was the Lord’s doing,

and it is amazing in our eyes”?

43 Therefore I tell you, the kingdom of God will be taken away from you and given to a people that produces the fruits of the kingdom.[b] 44 The one who falls on this stone will be broken to pieces; and it will crush anyone on whom it falls.’[c]

45 When the chief priests and the Pharisees heard his parables, they realized that he was speaking about them. 46 They wanted to arrest him, but they feared the crowds, because they regarded him as a prophet.

This is the Gospel of the Lord

Praise to you, Lord Jesus Christ.

In the name of the Living God, + Creator, Redeemer and Spirit.

Amen.

From Psalm 24:

The earth is the Lord’s, and everything in it. (Psalm 24:1)

Ngaala kaaditj Noongar moort keyen kaadak nidja boodja

We acknowledge the Noongar people as the original custodians of this land.

I have a special reason this morning for acknowledging that we are walking on the land of the Whadjuk people here in Noongar country near the border of the Pinjar Noongars.

There is something powerful and mysterious to reflect that human feet have trod this part of God’s world for at least 40,000 years.

I’d like to take you back just 65 years to Tambellup School, 80 kilometres north of Albany. I went to this school for seven years along with 200 other kids. About a quarter of the students were Noongar children.

One day when I was about eight, a group of three or four of the Noongar kids said to me that they had something special to tell me – but it had to be outside the school grounds. I was a well-behaved kid, so they must have been persuasive, because I found myself outside the school in the scrubby sandy country with the Noongar kids.

They told me an exciting story. I didn’t understand much of it, but I gathered it was about their grandparents being shot at. Some were very brave. Some hid in the river. Others ran away. One or two of the old men threw spears.

The same thing happened to me when I was about 11. Different kids, same story. I understood it more this time around. A band of white men on horseback attacked an Aboriginal camp. As they shot indiscriminately into the people for a full 90 minutes, an hour and a half, the frightened Noongars ran. The only way they could go was to the Murray River. They were forced into the river. Some hid in the water for hours using reeds to breathe. Others ran away. They were all brave.

I eventually found out that this event is known as the Pinjarra Massacre. The stories I heard were so vivid, I thought they were describing events in the life of their immediate grandparents, in 1934, but the shooting of perhaps 30 Noongars, maybe more, actually took place in 1834, just 30 minutes from here.

When I started putting these events into the context of European settlement and the taking of Noongar land, I found I wasn’t the only one to hear this story growing up. Other West Australian kids had had the same experience in the 1950s.

It seems to me this was a plan: to encourage Noongar kids to tell white kids the story of the Pinjarra Massacre, and to encourage us to tell other white people the story.

What amazes me is the tone in which this story was told to us. It wasn’t an accusation. It wasn’t to make us white people feel guilty. It was so that we would see the story from their side. It was to acknowledge that this is our shared history. It was to declare that the Noongar people want to walk side by side with us.

When they say, ‘Welcome to country’, they mean it. ‘We want to make peace. We want you to walk on our land together with us. We welcome you.’

If I have heard that message of welcome correctly, it’s amazing. The Pinjarra Massacre, as you know, was not the only mass killing of Noongar people near here.

Ambitious Lieutenant Bunbury making the road ‘safe’ for travellers heading south from Perth, led two mass shootings. One, which took place near York, was so ferocious that the Swan River Guardian in 1837 reported it as ‘Barbarities of theMiddle Ages.’[i]

… and they named the city after the young Lieutenant!

Where we used to live in Busselton, we learned that, on two occasions at least, settlers killed numbers of Wadandi Noongars each time in retaliation for a settler being killed.

Of course, I am not saying that the Noongars like what Europeans have done to them. Of course not. Mass killings to drive the First People off their land has meant that today – in 2023 – more of them are locked up, more of them die young, more of them have poor health and low levels of education. They grieve all that has happened and is still happening. It creates a burning anger. Noongars have every right to resist, and they have done in the past and they are still fighting. Yagan is a hero for a reason.

But each time violence is done to them, Noongar people still say, ‘We welcome you.’

To go on inviting us to peace, over and over again; this is crazy brave, and, I think, quite amazing.

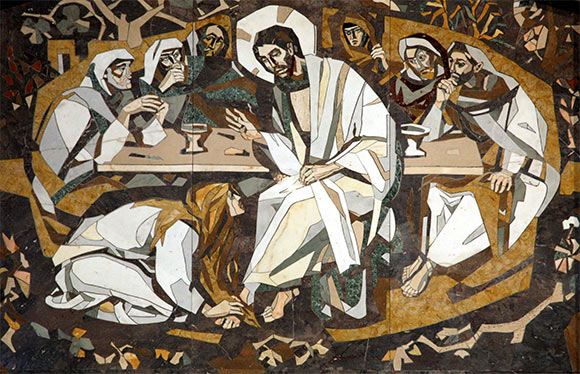

The parable Jesus tells in this morning’s gospel is about the violence that the tenants in the vineyard inflict on the servants the landowner sends.

‘When the harvest time had come, he sent his slaves to the tenants to collect his produce. But the tenants seized the slaves, and beat one, killed another, and stoned another. Again he sent other slaves, more than the first. And they treated them in the same way.’ (Matthew 21:34-37).

Over and over. Slaves come. They are beaten. Others come. They are stoned. Others are sent. They are killed. The tenants inflict violence over and over. Finally, the landowner sends his son. They throw the son out of the vineyard and kill him.

When you hear this parable the first time, it seems to be about violence. The story shows the violent end that will come to people who live by violence.

But what if the parable is not mainly about the tenants and their violence?

What surprises me about the parable is the landowner’s actions. Right from the beginning we see that how patient this landowner is.

Anyone who plants a vineyard is patient.

My brother Jim decided to grow grapes on his farm at Broomehill. He planted the grapes and fenced the area. He tended the grapes. He attended lessons on viticulture at Harvey Ag. It was four years before he got any kind of harvest, and a couple more years before he could sell his own vintage. If you’ve ever been to Broomehill and bought Wadjekanup wines or Henry Jones port, you will have enjoyed the result of Jim’s patience.

So this landowner in today’s story is prepared to wait for his vines to bear fruit and produce wine. And then, when he thinks he can collect his share, his servants meet violence after violence. And what does the landowner do? He sends more servants. And then what does he do? He sends more servants. Even if they are only slaves, they are worth something. It’s extravagantly expensive to lose so many servants. It must break his heart each time. But he keeps sending them. Despite the repeated violence, the landowner still believes he can do business with the tenants.

In this way, the landowner is like God. God comes, God invites Godself into the life of his vineyard, over and over again.

God sends servants to us. Moses, for example. We keep hearing about Moses and the Ten Commandments. And we need to. The Ten Commandments are like a fence for the good life. Moses invites us to keep within those boundaries. But it’s so easy to say, ‘We don’t need moral guidance. We know what is good.’ We reject Moses. But God keeps sending him. At least once every three years in the lectionary, Moses pops up. God reminding us of the good life.

And poor Moses. Having led the people of Israel to within sight of the Promised Land, Moses dies on Mount Nebo before he can enter the new land.

God sends other prophets. Jeremiah is a whistleblower who speaks out about corruption. He ends up dropped in a dry well and then exiled to Egypt.

And on and on, through the Old Testament, and still after the time of Jesus.

God keeps sending servants. Last Wednesday, we celebrated the feast day of Saint Francis of Assisi. For me, St Francis is a special prophet.

Through him, God reminds us that all of creation is our sister or brother. Through St Francis God reminds us not to be sucked into consumerism and greed. We need God to go on sending prophets like Saint Francis. Just look at the polluted environment we live in. Just look at the greed that capitalism engenders.

But for all his positive message, Francis ended up ill with malaria, managing the wounds in his hands and sides from the stigmata, coping with blindness and stomach complaints.

I think God is crazy brave, continuing to send us his servants. God is like the Noongars, continuing to invite us into their story, despite our repeated violence to them.

But finally in the parable, the landowner sends us his son. The son is treated no differently from all the other good servants. But we know now that there is a different ending for the Son of God. His death and resurrection are a signal from that the cycle of violence does not just go on and on. God will bring it to a joyful end.

So what is Jesus teaching us in this parable?

Firstly, that God is so generous. God keeps sending people and signs and messengers of all sorts to make sure that you and I know God’s love.

We are full of gratitude that God takes so much trouble to reach each one of us. This morning, as every Sunday morning, God comes to us in the bread and the wine, God’s presence among us and within us. We thank God for God’s persistent love.

Secondly, we too are God’s servants. We may find ourselves called to be messengers of God’s persistent love to others. We see the young Mum in the shops with a baby in her arms and a rebellious toddler screaming her lungs out. We can express sympathy. We’ve been there before. We might even find a way to help her.

Or a relative comes to talk to us about their faltering marriage. We listen. We may even dare to offer some advice.

Or we meet someone with a terminal diagnosis. We hesitantly find the words to say that, in Christ, death is not the end of the story. That God’s love goes on forever, in a more glorious fashion than we can begin to imagine.

Of course, when we are called to be a messenger, there’s a cost. The young Mum may angrily refuse our help. She may misunderstand our intentions.

Other members of the family may resent our intervention in someone’s marriage.

When we try to express God’s love for someone on the journey to death, we trip over our own grief, and our own fears. It hurts us, too.

We just sang William Vanstone’s hymn,

Love that gives, gives ever more, …

spares not, keeps not, all outpours. …

Drained is love in making full, …

weak in giving power to be.

But God gives us the grace to go on being God’s persistent messenger of love. And, whatever the cost, we know ourselves to be more and more deeply immersed in God’s love.

Let us pray the prayer attributed to Saint Francis of Assisi.

Lord, make us channels of your peace:

where there is hatred, let us sow love;

where there is injury, pardon;

where there is discord, union;

where there is doubt, faith;

where there is despair, hope;

where there is darkness, light;

where there is sadness, joy.

O divine Master, grant that we may not so much seek

to be consoled as to console,

to be understood as to understand,

to be loved as to love.

For it is in giving that we receive,

it is in pardoning that we are pardoned,

and it is in dying that we are born to eternal life.

Amen.

[i] Barbarities of the Middle Age have been committed even by boys and servants, who shot the unarmed woman, the unoffensive child, and the men who kindly showed them the road in the bush; the ears of the corpses have been cut off, and hung up in the kitchen of a gentleman, as a signal of triumph.

The Swan River Guardian, 16 November 1837,

Quoted in

says a pregnant woman listens to the child in the womb and learns a song that is unique to that child. She teaches the father-to-be the song, then she teaches the midwives who sing it as the child is born. As the child grows up, each time the child falls and hurts herself, the village gathers around and sings her song. When she does something wrong as an adult, she is brought face to face with those she has wronged, the villagers form a circle around her and sing her song. The song is sung at the person’s funeral, and then is never heard again.

says a pregnant woman listens to the child in the womb and learns a song that is unique to that child. She teaches the father-to-be the song, then she teaches the midwives who sing it as the child is born. As the child grows up, each time the child falls and hurts herself, the village gathers around and sings her song. When she does something wrong as an adult, she is brought face to face with those she has wronged, the villagers form a circle around her and sing her song. The song is sung at the person’s funeral, and then is never heard again.