The tips of icebergs are notoriously dangerous: the old saying posits that nine-tenths of the iceberg is under the water. This larger invisible ice stabilises the whole ice structure. Ignoring them is a dangerous choice.

In the past few days politicians have been bandying about the phrase ‘Islamic terror hatred’. They state that preventing such hatred may prevent further shootings. The Government are proclaiming victory. Their new law will make Australian Jews safer.

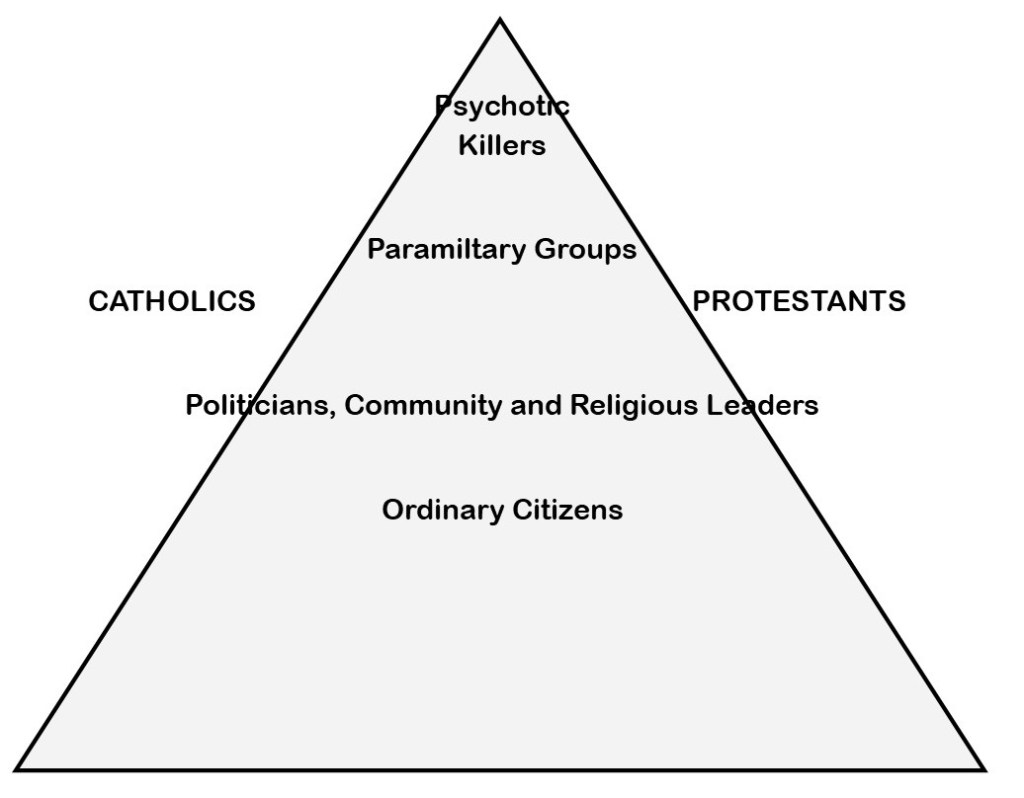

That may be true – as far as it goes. There is a great deal going on ‘under’ the tip of the iceberg: the psychotic killers who use Islamic language to justify their criminal actions are only the visible iceberg. Laws condemning such statements should have some effect. Reducing the number of guns in the community may also reduce opportunities for killers to act.

These psychotic killers are buoyed by hate groups. Neo-Nazis spout hatred of Jews. I note that they are not Islamic terrorists, but nasty just the same. ISIS may not be an identifiable group in Australia, but its hate speech empowered the killers at Bondi. These militant groups may not be killers, but they give permission to the few who are.

But drill down further into the iceberg, into the Australian community. Politicians, community leaders and religious leaders, myself included, have not been strong enough, persistent enough and clear enough in our condemnation of these hate groups.

As a Christian priest, my clear task is to promote the truth that every person, regardless of race, religion, ethnic background, is made in God’s image, beloved by God, and therefore worthy of respect. God loves each person and weeps over every instance of discrimination and hatred. God doesn’t tolerate it.

Other faith and community leaders may express these values differently. Even these differences are wonderful and to be welcomed.

Our lack of leadership gives permission to the hate groups. We need to own the fact that our condemnation of them has not been strong enough.

And of course, leaders can be strong in promoting community harmony only if the community itself encourages us leaders to speak out against hate and for respect.

As we drill down even further, into the general community, we should examine ourselves: are we harbouring discrimination in our hearts? Are we tainted by not accepting difference ourselves? These are uncomfortable questions, and lead to other questions even more discomforting: do we call out casual racism when we hear it? Do we show acceptance to those of different skin colour or strange religions (strange to us)?

My assessment is that we participate in a society that fails to live up to its values of acceptance and compassion. I cringe when I recognise the sting of the discriminatory attitudes I grew up and I catch myself flinching from different skin colour or distinct dress.

We are a racist mob. And for as long as we don’t challenge it, we let our leaders off the hook. They, in turn, avoid difficult conversation. They fail to condemn. They, in turn, give power to the rhetoric of the hate groups, who, in their turn, give cover to those who would use their rhetoric to kill.

One law won’t stop ‘Islamic terror hatred’ or anti-Muslim diatribes. There’s a rottenness running through our whole society. Of course, not every individual is a racist, but too often I find myself willing, by inaction, to participate in it.

As well as laws against hate speech, we need education for harmony. That is a huge task to get on with, but it is a possible remedy to the danger of the iceberg. The choice to do nothing through every part of the community is the choice to run into more horror like that on the beach at Bondi.

Pyramid courtesy Northern Ireland Mediation