If you prefer to listen to Ted preaching this homily, click below (12 minutes):

The Holy Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ according to Saint Luke.

Glory to you, Lord Jesus Christ.

[Luke 17:5-10]

5 The apostles said to the Lord, “Increase our faith!” 6 The Lord replied, “If you had faith the size of a mustard seed, you could say to this mulberry tree, ‘Be uprooted and planted in the sea,’ and it would obey you.

7[Jesus said], “Who among you would say to your slave who has just come in from ploughing or tending sheep in the field, ‘Come here at once and take your place at the table’? 8 Would you not rather say to him, ‘Prepare supper for me; put on your apron and serve me while I eat and drink; later you may eat and drink’? 9 Do you thank the slave for doing what was commanded? 10 So you also, when you have done all that you were ordered to do, say, ‘We are worthless slaves; we have done only what we ought to have done!’”

For the Gospel of the Lord,

Praise to you, Lord Jesus Christ.

In the Name of the Living God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

The whole point of having a slave is that person can do whatever you want whenever you want.

When we were in Mauritius Rae and I used to worry about our hosts’ driver who was called Anil. Our hosts owned a sugar plantation and invited us to dinner a couple of times during our seven-week stay on the island.

They would send a message ‘Anil will pick you at 5:30.’ Anil arrived promptly at 5:30. Anil drove us back to the plantation. We had dinner, not with Anil, of course. Just with Pierre and Doris. Pierre showed us over their sugar refinery, a 24-hour operation. We talked. At 11:30 in the evening, it was time to go home.

Pierre yelled across the backyard, ‘Anil! Anil!’ Anil stumbled out of his hut, shook off his sleep and drove us home. It was an hour’s drive, and then, of course, Anil had to drive an hour back again.

Anil wasn’t a slave, but Rae and I worried that he was treated like one.

The people of Jesus’ time had slaves. The Jews had always had slaves, going back to the time of Abraham. At least, the more affluent Jews had slaves. And the whole Roman Empire depended on the labour of slaves. Apparently one third of the population was enslaved. People 2,000 years ago didn’t have the same moral objection to slaves that we have now.

And the whole point of having a slave is that person can do whatever you want whenever you want.

In this morning’s Gospel reading, Jesus invited the people of his day to try a radical thought experiment: imagine you are the owner of a slave who has been ‘working all day in the field, ploughing or tending sheep.’ (Luke 17:7) When evening comes, you allow the slave to take as much time as he wants to wash and change into clean clothes. Then the slave reclines on the best dining couch in the house. Then you, the owner, the master, serve the slave his dinner, and the slave can eat the meal quickly, or can spend four or five hours at the table chatting to friends and drinking wine. You are on call until the slave tells you he has finished his meal.

Then Jesus stops the thought experiment. No: you treat the slave as a worthless slave whose job is to serve you and not the other way around. If it doesn’t suit the slave or the slave is too tired makes no difference.

This thought experiment comes from Jesus, who as Saint Mark and Saint Matthew tell us, ‘…came not to be served but to serve and to give his life a ransom for many.’ (Mark 10:45, Matthew 20:28). Not to be served, but to be a slave.

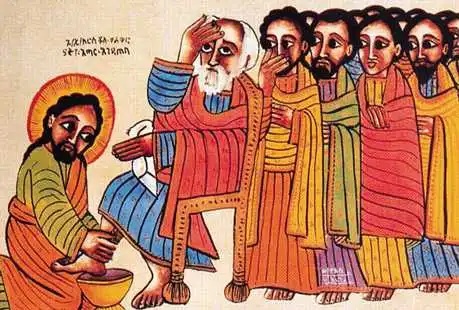

In other words, this thought experiment is not as fanciful as it sounds. Jesus himself swaps the role of Lord for that of a slave for example, when he washed the disciples’ feet (John 13:5), and really upsetting Simon Peter. ‘You will never wash my feet!’ wails Peter (John 13:8).

It’s not possible, we think. Even if you don’t own a slave, the point of having slaves is to do anything their masters want at any time. Jesus upends this idea. A slave is a human being created in the image of God, and simply because of that should be, at least, respected. But more than just respecting slaves, Jesus challenges us to serve others as if we were slaves ourselves. And especially, we should serve those who are treated as slaves.

Yesterday was the feast of Saint Francis of Assisi, a saint who means a great deal to me. Francis was the son of a cloth merchant, Pietro di Bernadone, who was growing richer and richer. Francis was privileged by having the benefit of this extreme wealth, and when he was a teenager, he made the most of the lavish lifestyle. He threw wild parties with his friends, providing the wine and food for the feasts. He gained the nickname ‘The King of The Revels’.

But he grew uncomfortable with this privilege. He was riding outside Assisi one day – and owning a horse was something like owning a Morgan Super 3 sports-car today or maybe a Rolls Royce Sweptail with a million-dollar price tag. As he rode, he saw a leper. Until then, Francis had been revolted by lepers. They were disgusting, repulsive. But on this day, Francis was moved to dismount and approach the leper and embrace him. Something changed in Francis from that moment. ‘That which was bitter had become sweet,’ he wrote later. (The Testament, 1, FAED I, 124.)

One of the first ministries Saint Francis undertook was caring for lepers; becoming their slave, their servant, looking with love on their distorted features and running sores, feeding them, keeping them safe from brigands and dressing their wounds.

Francis knew that this was how Jesus challenges us to be a slave to others. It’s a confronting idea. And we should be confronted. It goes against the way things are. It turns the world upside down.

I find it interesting that even though Francis is known for poverty, in the early years, many of his followers were queens and princesses: the Blessed Isabelle of France, Saint Louis’ sister, was a princess, and Saint Elizabeth was the wife of the future king of Hungary. Saint Clare too was from a noble family. These royals and aristocrats responded to the challenge to become a slave for others, serving the poorest, putting their lives at the service of the neediest.

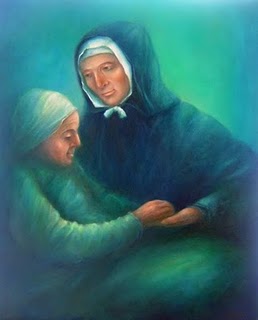

I am impressed by Saint Jeanne Jugan in France just after the French revolution. She was inspired by Saint Francis to look after homeless women, eventually setting up a network of refuges throughout the east of France and becoming the Little Sisters of the Poor, who are in 2025 still serving the elderly poor. They have a house in Glendalough just north of Perth city. She too, and her sisters, respond to the challenge to be a slave to others.

And we are followers of Jesus too. The same challenge applies to us – as individuals, as the people of Saint Brendan’s. We don’t have to be the founder of a religious order, or even join one, to take up this challenge of Jesus. But if royals and aristocrats can become slaves, so can you and I.

Is there some situation where God is calling you to be a slave? Is there a person whose needs you can try to meet, but whom you avoid because you know it will be difficult? Is someone you know being held captive, ensnared in some way by someone? Is there a way to be a slave to them, to serve them in their needs? Being a slave is not about knowing you can succeed. It’s about putting aside our needs to achieve, to make a mark. Being a slave’s only about obeying the master. ‘When you have done all that you were ordered to do, say, ‘We are worthless slaves; we have done only what we ought to have done!’” (Luke 17:10)

And our ultimate Master is Jesus, and Jesus chooses to serve when others are certain it’s beneath Him.

As a parish community, we rightly hold up our ministry to the Homeless as one example where we put energy and care into serving others whatever their needs. But just because we are serving one needy group does not mean there are not others in the Warnbro/Rockingham community calling out for our service as a parish.

Today we bless our pets. The same challenge applies to animals as it does to human beings. We sometimes think of our pets as slaves. We keep them locked them up in our house or yard. We have them on a leash when we take them outside. We expect them to do emotional work for us, loving us when we come home from being away. But I am sure that we bless our cats and dogs because we know the challenge to be a slave to them too. Take note of that Lottie, and Caesar.

So this story in the Gospel about a slave coming in from a day’s work in the field is not a hypothetical. It’s a challenge. It confronts us to find ways in which serving others turns the world on its head and creates a kinder, more loving world in partnership with the One who came to serve.

Where is God calling you to be a slave today?