Sermon for St Brendan’s-by-the-Sea, Warnbro [Diocese of Perth]

Readings:

Isaiah 58:1-14

1 Corinthians 2.1-7,9-10a,13a

Matthew 5:13-20

To hear Ted preach this sermon, click here:

In the Name of the + living God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

You may have heard of the new priest in a parish. (Not this parish, of course). The nominators had assured the parish that she was a good preacher, so the congregation looked forward to her first Sunday. She preached about ‘love’. After the service, the wardens and nominators congratulated her, saying what a nice sermon it was.

On the next Sunday, they were surprised to hear the priest preach the same sermon, word for word, on ‘love’. The wardens and nominators said among themselves, ‘Well, she has been unpacking and getting her kids sorted for school. We won’t say anything today, but we will look forward to the next sermon.’

On her third Sunday, the priest again preached the same sermon. The wardens said to her, ‘We understand you’ve been busy settling in, but we are surprised to hear the same sermon week after week.’

‘And I’ll go on preaching it,’ she replied, ‘until you get it… and act on it.’

I feel a bit the same with today’s sermon. I seemed to have preached it many times over 50 years. And the challenge is the same. Jesus commands us to love God and love our neighbour, especially the vulnerable neighbour. I’ll go on preaching it, I guess, for the same reason as the brand-new Rector. We all, myself included, need to really get it – and do it!

It’s easy to be angry or depressed about the world around us. I definitely won’t talk about that man, although his actions are making things worse.

I won’t use his name either. There’s a family connection here: my beloved Rae’s mother grew up in Nazi Germany. ‘Zat man,’ she used to say about a different power-drunk man. I never heard her use his name. ‘Zat man took away our vote. Vot zat man meant was zat ve didn’t have enough to eat.’

As to today’s world, I won’t mention that man in America again. As you will see, I won’t need to.

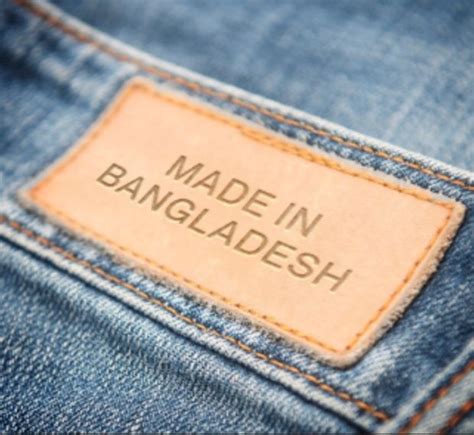

Who makes the clothes we wear? A 2025 Oxfam Australia report states that children in Bangladesh are making some of those clothes. Children are subcontracted out, so their names don’t appear on any payroll. And Bangladeshi adults, too, are forced to work. Under intolerable conditions, 10 or 12 hours a day, and refused bathroom breaks. 95% of the factory workers are paid below a living wage, and for women, that figure rises to 100%.

These conditions amount to slavery. At the very least, they are ‘the bonds of injustice, … the straps of the yoke, … the oppressed.’ (Isaiah 58:4) The very conditions Isaiah railed against two and half millennia ago.

You have all answered your phone to unknown numbers where the callers spoke in a South Asian accent and harassed you to put money into some scheme or repay a debt (that you didn’t know you had) and told you that you had to transfer the money today, in two hours’ time. If you get a call like that, put the phone down. It’s the wisest thing to do.

It’s a sad reflection of today’s world that we have to be alert to these scams. There is another tragic side to the story. Many of these scam call centres are run by international criminal groups. The callers may be young Indians lured to Dubai by the promise of real jobs in construction. Instead, the gangs traffic them to countries as far apart as Myanmar or Peru, lock them into substandard accommodation attached to the call centres, and force them to make these calls in cramped conditions, hour after hour, shut into a tiny world by their headphones.

These conditions also amount to slavery. INTERPOL is one of several agencies tracking down the criminals and having them tried in court.

Closer to home, one in seven Australians lives below the poverty line, defined by ACOSS, the Australian Council on Social Services, as half the median income. So, 15% of us bring in less than $40,000 a year. Now, $40,000 is fine if you own your house, you share it with a spouse or partner, and you have some savings, and you’re eligible for a Support at Home package from the government.

But if you are single, not a homeowner, with no savings, $40,000 means you struggle to pay up to $15,000 for rent, and find the money for food, air-conditioning, and out-of-pocket medical expenses. And because WA has the highest incomes in the country, prices here can be higher than elsewhere, making it even more difficult just to live with dignity.

There are over 3,000 homeless children in WA. So reports the Youth Affairs Council. 60% of those young people are LGBTIAQ+. From 2013 to 2023, 52 children known to the Specialist Housing Service have died. That’s two kids a year. Around Australia, 177 children have died on the streets over a ten-year stretch. Nearly 18 kids under the age of 14 every year.

This means that ‘[s]haring you bread with the hungry, bringing the homeless poor in your house,’ and providing clothes for the winter cold (Isaiah 58:7), are challenges for us Christians, for us as Australians.

Here in the City of Rockingham, a group of agencies nominate homelessness, mental ill health, and family and domestic violence as the main three social needs of people in this suburb.

Isaiah’s words describe our world so well:

Is not this the fast that I choose:

to loose the bonds of injustice,

to undo the straps of the yoke,

to let the oppressed go free,

and to break every yoke?

7 Is it not to share your bread with the hungry

and bring the homeless poor into your house;

when you see the naked, to cover them

and not to hide yourself from your own kin?

Isaiah 58:6-7 NRSVue

Does this sound like Good News? Maybe not. But Isaiah commands us not to turn our eyes away. And not to harden our hearts. The world’s problems are our problems. Working for social justice is essential for us as Christians, as people of faith. It’s not an optional extra.

Good News is found in this morning’s Gospel reading. We are to be salt and light. We are to change the world for the better, like salt improves the taste of food. We are to bring light to dark situations. Salt and light. It sounds simple.

And not one little, teeny bit of the Old Testament is abolished by Jesus. Not one requirement of the Law and the Prophets. And the Prophet this morning roundly condemns people who do nothing to make the world more just. Isaiah also criticises hypocrites, who profess they are helping the disadvantaged, but they do nothing.

The prophet backs us into a corner. Helping the disadvantaged is not an option for people of faith.

But here is Good News.

If God has favourites, they are the poor. The Risen Christ proclaims that the future belongs to him. The poor are blessed because Christ is reversing their plight. The Spirit of Christ empowers us to collaborate with him. And what collaborations there have already been! We can see injustice. But we can also see how Christian people have responded to the call to be salt and light.

We think immediately of this parish’s respite for the homeless. It’s good news for those doing it tough, and it’s good news for the volunteers. Just ask them how they feel about their role at ‘Homeless’.

I think of Anglicare WA. Good News for many suffering from the selfishness of our wealthy society. Every Diocese in the Australian Church has an Anglicare, people working with Christian motivation to relieve the suffering of poverty. It is Good News.

I think of the West Australian organisation Ruah. Its name means ‘Spirit’ in the Hebrew of the Bible. Ruah is carrying on the work of the Daughters of Charity, a Christian Order in the Roman Catholic church. Ruah works especially with people with mental health challenges. It has wrap-around services for the homeless. It makes sure that Indigenous people are appropriately cared for. It’s Good News.

I think of EPIC Assist in the Eastern states, supported by the Anglican Franciscan Brothers, especially Brother Donald Campbell. E.P.I.C., Enabling People in Community, works to provide employment for people with disabilities. Its work has expanded from Queensland to Scotland and Croatia. Good News.

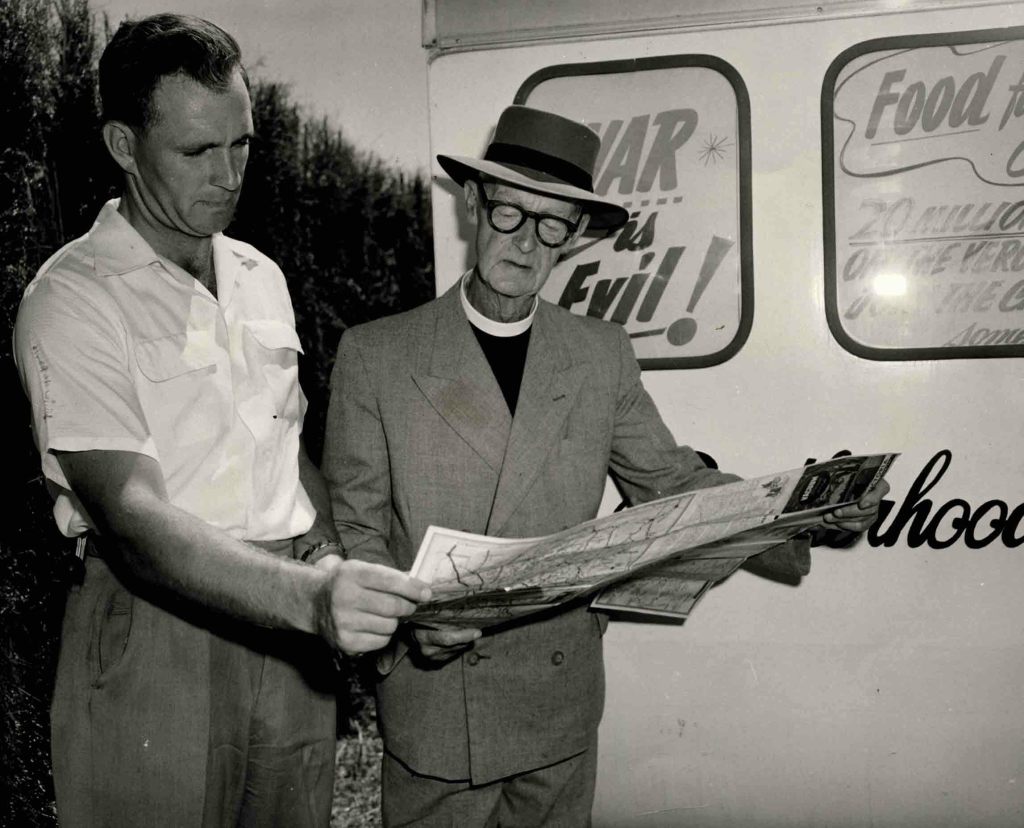

Father Tucker, Founder of the Brotherhood of Saint Laurence, Melbourne

I really admire the Christians in Minneapolis who have the courage to take peaceful action to curtail the cruelty of the ICE immigration agents.

Some write letters to the authorities. Groups of Christians protest noisily outside the hotels where ICE agents are staying.

Some blow whistles when ICE agents arrive in a neighbourhood. Others, like the young mother, Renee Good, follow them in their cars. Others, like nurse Alex Pretti, are filming their activities. I see that God is at work in his people in Minnesota.

We know, in our hearts, that there could come a time when God would call us to do similar. Pray God it doesn’t. But if it does, God will give the strength and courage we need. That’s the Good News in a bad situation.

All of these and so many more are Christians acting together and also working with others of good will, to

to loose the bonds of injustice,

to undo the straps of the yoke,

to let the oppressed go free,

and to break every yoke.

Isaiah 58:3.

The Good News in all this is that Christ is with us.

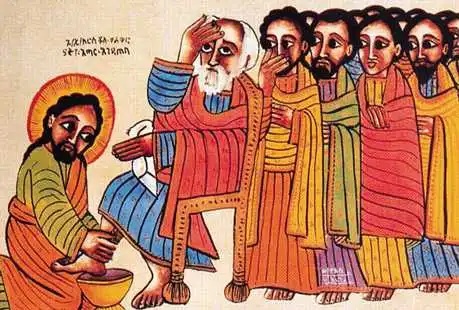

In the Eucharist this morning, as every Sunday morning and all around the world, a body is broken. Blood is poured out. The Risen Christ is with every body broken in slavery. The Risen Christ is with every Gazan or Ukrainian or Sudanese whose blood is poured out.

What is more, the powers-that-be, the rich and powerful who are crushing the poor, they are critiqued. Their greed and cruelty are exposed. We see that man I will not name for what he is. Our poor attempts to change things is revealed. We come to confession, confessing the one true sin: our failure to love.

The miracle of the Eucharist is that we no longer need be angry and sad about the world. The broken body and blood poured out moves us first to compassion and then to hope.

The risen Christ empowers God’s people to act to bring positive change to those suffering from the unjust structures of our society.

As individuals, we can be aware of poverty, and we can be well informed as we pray.

God empowers us to do a variety of things.

- Support these organisations which have a Christian impetus…

By being aware of their work, by praying, by donating goods and money, by spreading the word, by volunteering.

- Be mindful of the good we can do…

By asking God for guidance.

What is God calling you to do? For example,

Be mindful in our shopping for clothes. How can we cause the least harm to Bangladeshi workers? Research supply chains. Buy fewer new clothes. Support Op. Shops.

- Understand the situation of those making scam calls. Answer those scam calls gently. Yelling at the caller only adds to their humiliation as slaves. Maybe ask them how their day is. Maybe tell them you’re sorry you can’t oblige them.

- Not walking past the homeless. We may not carry cash, but we do carry kindness. If someone is begging in the street, they’re desperate. And in the end, they are desperate for love, so we can choose to be salt and light for them. Money may or may not be helpful, but we can do a lot to restore their dignity by seeing them as a fellow human being. ‘Hello. How are you?’ is great medicine.

Be assured that our little acts of love, because we are empowered by the Risen Jesus, add up to make a difference. Be encouraged by Jesus saying, ‘Whatever you do to the least of these, you do to me.’ (Matthew 31:40) And where we fall short, the Spirit makes it up to be effective action. In the economy of grace, our five loaves and two fishes feed thousands. (See Luke 9:10-17)

And for those of us who are struggling to make ends meet, we can choose to be grateful for the kindness and ministry of others. We can all choose to recognise the hard times of the people we meet.

Take away from this sermon three ideas:

Be aware. Don’t turn your eyes away. God’s people are suffering. Be aware.

Prayer. It can be hard to pray. Let the Spirit pray in you and through you. But groups and individual Christians will be strengthened by your prayer.

Be aware. Prayer.

Dare. Dare to take action. Dare to give of your treasure, your time, your talents to make a difference in God’s world. Holy Spirit will empower you to be salt and light. ‘Don’t worry what you are to say or do, because the Holy Spirit is working through you.

Be aware. Prayer. Dare.

Ash Wednesday is 10 days away. We all need to begin thinking about this Lent. What kind of fast is God calling you and me to this year? Giving up sugar? Well, yes, it might be sensible. I need to cut down on sugar.

But today’s Good News is that our fast shouldn’t be about ourselves. The fast is not to focus on our own spiritual needs. Our fast can and should be pragmatic, hands-on action for others, not hollow words. Some suggestions for your Lenten fast are on the page below.

Isaiah goes on to say:

If you remove the yoke from among you,

the pointing of the finger, the speaking of evil,

10 if you offer your food to the hungry

and satisfy the needs of the afflicted,

then your light shall rise in the darkness

and your gloom be like the noonday.

11 The Lord will guide you continually

and satisfy your needs in parched places

and make your bones strong,

and you shall be like a watered garden,

like a spring of water

whose waters never fail.

Isaiah 58:9b-11

Good News indeed.

Some Suggestions for Doing Lent in 2026

says a pregnant woman listens to the child in the womb and learns a song that is unique to that child. She teaches the father-to-be the song, then she teaches the midwives who sing it as the child is born. As the child grows up, each time the child falls and hurts herself, the village gathers around and sings her song. When she does something wrong as an adult, she is brought face to face with those she has wronged, the villagers form a circle around her and sing her song. The song is sung at the person’s funeral, and then is never heard again.

says a pregnant woman listens to the child in the womb and learns a song that is unique to that child. She teaches the father-to-be the song, then she teaches the midwives who sing it as the child is born. As the child grows up, each time the child falls and hurts herself, the village gathers around and sings her song. When she does something wrong as an adult, she is brought face to face with those she has wronged, the villagers form a circle around her and sing her song. The song is sung at the person’s funeral, and then is never heard again.