Mat Osman, The Ghost Theatre: A Thrilling Adventure, Overlook Press 2023.

ISBN: 9781526654403. Hardback 313 pages

Paperback (Bloomsbury Press) from $20 online

In Public Library system

Reviewed by Ted Witham

The stage is illuminated by just four candles. A boat’s prow appears behind the curtain at the back. A blue cloth billows across the stage, making the boat appear to gyre in the waves. A firecracker above and the drum-roll of wood on metal rock the stage. Cleopatra appears in the bow of the boat. She waits her moment and then speaks. She knows her power. The prompt just below the front of the stage is thrown again as Cleopatra strays off-script.

But she knows her public.

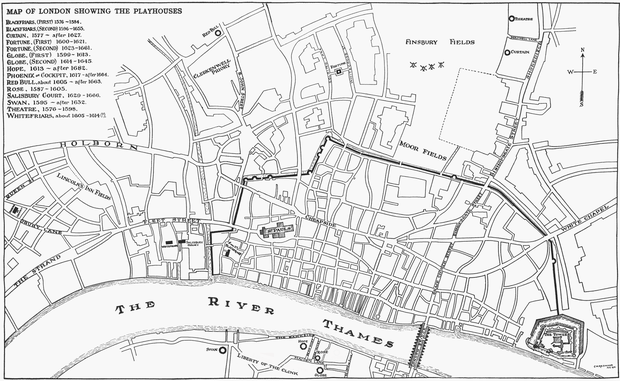

The fifty or so audience members are mesmerised by every word, every stage trick, everything that makes up the theatre experience in 1603 London.

The theatre in Mat Osman’s gorgeous novel is modelled closely on the real Blackfriars Boys, even to the extent that the impresario who owns the boys is named Evans (the historical Henry Evans held the licence for the Blackfriars).

The actor who plays Cleopatra so captivatingly is ‘Lord’ Nonesuch, a 15-year-old boy whose acting brings him fame, ‘name recognition’, throughout the 400,000 residents of the city. Adoring girls wait for him at the theatre door.

A dark side soon appears: the boys are forced to perform for parties at Evans’ house and the houses of other rich gentlemen. Nonesuch is painted white and stands on a plinth for the aristocrats’ diversion. Osman does not directly describe these tableaux; he appeals to our imagination to fill in the detail – or not.

In a clever misdirection, Nonesuch at first appears to be the main protagonist in The Ghost Theatre. He is so charismatic, and so much the leader of the boys (and girls) of the theatre, that Osman makes us admire him and worry for him. His backstory is dire. He is no Lord, but when he was ten, Evans bought him for sixpence from his drunken parents.

Shay passes as a boy to earn pennies as a messenger. She avoids the crammed streets by running the rooftops like urban runners in the 21st Century.

She lives on the marsh in Southwark. She and her dying father are members of the Aviscultans, a community outside the law (in Elizabeth’s England you have to be Church of England, or else), and is slated to take over from her late mother as the soothsayer who interprets the murmuration of the starlings. In the City, she hides her shaven and tattooed head with a cap.

She is so intrigued by her chance meeting with Nonesuch that she returns with him to the theatre and quickly becomes part of the little world of the boys and special effects girl Alouette and costume maker Blanch, a West Indian diver.

A quiet connection is established with Alvery Trussell, the quiet, clumsy boy who can’t quite learn his lines, and is everything that Nonesuch is not; at least in Nonesuch’s eyes.

Nonesuch is introduced to the rooftops. Their teenage romance is warm and beautiful. The other Blackfriars boys are generously happy for Nonesuch to share his cot with Shay in the dormitory.

Trying to gain a little freedom from Evans he and Shay set up pop-up theatres in pubs and alleyways, the Ghost Theatre. They had to be careful of the Queen’s enforcers, the Swifts, because theatre could only be performed with a licence.

They quickly make enemies. The villains in The Ghost Theatre are portrayed by the actions of their hoodlums; Gilmour’s men are after them, Elizabeth, the dying Queen deploys her Swifts with ruthless cruelty. Evans is ambitious in his cruelty. He is a thoroughgoing nasty man.

As their popularity grows, Shay and Nonesuch are inevitably drawn into these dangerous politics just as the plague hits. They flee the ‘sick city of 1603’ to perform in the country.

The politics and the relationships of the main characters pull the reader to a big dénouement involving a brutally repressed revolt of apprentices (in reality, the Tower Hill riot took place in 1595, so the novel skews the timeline – to good effect).

I loved this novel. The theatre world is drawn with careful detail, and the descriptions of London are alive and rich. The characters are all lovingly brought to life, and as the plot twists so do Nonesuch, Shay and Thrussell.

Historical fiction fans will enjoy this living, breathing, dirty, roiling London. Although teenage romance is at the heart of the novel, it is a book for all romantics. Shay and Nonesuch may be only 15 but, in order to survive in such a vicious place, they have a dignified maturity.

And, if you love theatre, you will savour the Three Acts of this Thrilling Tale. It is my standout book of 2023.

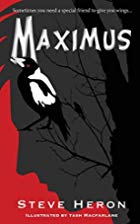

Steve Heron, Maximus, Serenity Press 2018

Steve Heron, Maximus, Serenity Press 2018