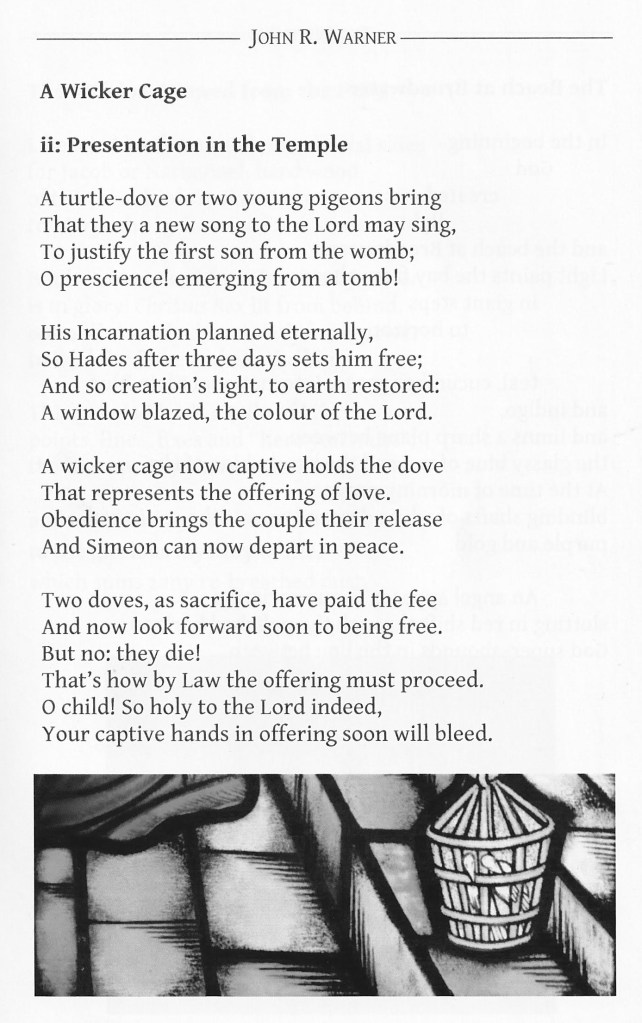

At Home in this Country

Noel Jeff’s two chapbooks reviewed by Ted Witham tssf

Noel Jeffs SSF, Ode to Warrigal Creek Massacre,

2025, A4 card folded.

ISBN 9780646826042.

Noel Jeffs, a Brother in the Society of Saint Francis comes from a farming family as I do. Settler folk like us cannot deny that our comparative wealth and social position derive from the dispossession of Aboriginal people.

The name Warrigal Creek in Victoria, like Pinjarra in WA, and doubtless similar names in other States, resonates because of the massacre perpetrated there. The name produces a complex amalgam of emotions, which Brother Noel explores in this poem.

Hope for reconciliation of country seems to be blown away by the ‘hot anger of a tied-up dog’ (line 3); shame for these murderous acts follows, and ‘now in pain I knead this atrophy’. (line 11). This line describes the violence with which the recollection of Warrigal Creek is turned over in the poet’s mind, like pushing, smoothing, pulling, pounding, tearing and restoring flour and water when making bread. The word ‘knead’ is a homonym for ‘kneed’, and I take from this that the poet’s rumination brings him to a silent place of kneeling in penitence.

The last and biggest emotion is ‘grieving’, grieving that the ‘litter of bones’ (18) may let the poet’s shame be revealed.

But hope seeps through the crammed lines of the poem. The insistence that this is ‘my country’ is used here to recognise the shared pain of remembering. It is ‘country’ as named by its original inhabitants, but it becomes ‘my country’ when truth is revealed.

The poem is printed on one A4 card folded. The front depicts four rainbow serpents entwined in a circle. The heads of the snakes form a cross with the word ‘sacred’ inscribed four times on the circumference. Printing in black and white has made the symbol rather harsh. References to the full story of the Warrigal Creek massacre are on the front and back covers.

The card would make a suitable emblem of remembrance for participants in a day of truth-telling, especially about the Warrigal Creek massacre. I commend Brother Noel for this brave contribution to the national and necessary task of truth-telling, This poem on its card is ‘a plaque to heroically // scold’ (13-14)

The Angelus and Mudbricks

Noel Jeffs SSF, Roads to Stroud: Grasping at Tears, Precipices, Sydney, Darkstar Digital 2024, 19 pages

Brother Noel’s chapbook consists in two poems of just under 140 lines each, describing the journey taken by the poet from the city into the bush of the Hunter Valley in NSW.

The Stroud of the title of Brother Noel’s poems needs some explanation as Stroud figures large in the imaginations of Australian Anglican Franciscans.

Nearly 50 years ago, three Anglican Franciscan nuns from the Community of Saint Clare in England arrived in Stroud in NSW with a vision to build a house for the Community. A small block of land just outside the town of Stroud was sold to the Sisters. Under the leadership of Sister Angela, an Australian, the Sisters, with volunteers helping, made mudbricks and constructed them into a unique building – a monastery with almost no straight lines but a lot of character.

A Chapel and Hermitage for the Brothers, initially for the priest-brothers to provide chaplaincy to the Sisters, was constructed 100 metres away from the monastery.

Since then, all three branches of the Franciscan family have made deep connections with this small section of attractive bush. Some of Noel’s fellow-Brothers make their home here, and Third Order members have enjoyed the rich hospitality of the place. Sadly, the Sisters returned to England in 2000, but memories of them are strong, especially in the old monastery, now a retreat house imbued with prayer.

In Brother Noel’s second poem under review, Precipices, ‘mudbricks and mudbricks’ (p.14) and the Angelus bell of the Chapel (p.16) take us straight to the property at Stroud. (It may also be intentional that the grey cover and simple typeface mimic the covers of the Sisters’ booklets of poetry and spirituality back in the 70s – a fitting homage!)

Noel Jeffs’ writing is thick with classical, Biblical and Franciscan allusions giving the whole experience of the poet’s visits to Stroud a nuanced exploration of ‘this parade of // fervour to want to come back year, // after year’.

The poet’s experience of leaving the city ‘awash with railway yards // tracks to sentience and homely inner-city birds’ (page 3) and arriving at Stroud where he finds it ‘ensconced in // its wilderness of wildness, made a // garden estate.’ (15)

The natural world and the human world are as entwined in the city as in they are in the country.

When the first Europeans arrived in NSW in 1788, some described the ‘natural’ parklands, the result of many thousands of years of land care by the Indigenous inhabitants, as a garden estate, so there’s a double irony in Jeffs’ description. Stroud, with its beautiful curated gum trees and mown grass, is a ‘garden estate’ hewn from wilderness.

The ‘loss’ of wilderness (or the Indigenous parkland?) is claimed with ‘a black fella warrior stood here // beckoning on, welcoming us in // in a vision.’ (15), the word ‘vision’ doing double duty here for physical vision and insight.

Jeff’s language is oblique. Words slip from meaning to meaning. As the poet is travelling north, watching the illusion of staying still in the train and seeing the bush moving, he asks, ‘What do I want to say about // the cantering bushland which // surrounds and is enveloped // by a tunnel of true darkness // which shapes my life in all its // passages?’ (12) The bush is cantering by as a horse canters, but it is also ‘canted’, (‘written slant’ as Emily Dickinson would say), so that it describes both the scenery and the poet’s inner feelings.

I relish the musicality of Brother Noel’s verse. He is a master of assonance which ranges from pure rhyme to distant echoes of sound. Savour the repeated ‘s’ , ‘p’, ‘ps’, and ‘l’ sounds in these three lines:

‘The circumference is here, and no longer

lying lips, give me a platypus and make

them safe.’ (13)

Simple in intention, the poems describe a journey home. But where is home, and what does it mean? The city ‘in which I am free // and lucky to be alive’ (1), or Stroud, where ‘I have gone to heaven, and am // coming down on the other side // of the earth’ (14)?

The archetypal ‘snakes [which] make love on poles’ (3) are a striking and original image, but they are surely meant to evoke the Caduceus, the staff of Mercury, the messenger of the gods, and widely used as a symbol of medicine. In ‘Grasping at Tears’, the poet is going to Stroud, and with him the messenger of the gods, a diplomat, the bringer of medicine, peace and healing. But the Caduceus also speaks truth with deception. The poet is an unreliable messenger, and his message is a rich potpourri of ambiguous imagery, alluring music and insights almost made explicit.

The poems are introduced by two fine photos taken by Brother Noel, the first shows the gravel road into Stroud, and the second a butcherbird enjoying her reflection in the outdoor shaving mirror at the Hermitage.

The poet may be ‘Grasping for Tears’, but it is unclear whether the tears are tears of sadness or tears of delight – probably both. I find the two poems ultimately hopeful, as the poet claims that:

‘Home is a handsome place

an exotic space for silence

A limbering tree-house (5)

***

Ode to Warrigal Creek Massacre and Roads to Stroud are available direct from the author, Noel Jeffs SSF, at noeljeffs@hotmail.com.

well, Drinks with Dead Poets: The autumn term, Oberon Books, 2012. Hardcover, 200 pages.

well, Drinks with Dead Poets: The autumn term, Oberon Books, 2012. Hardcover, 200 pages.