Candida Moss, God’s Ghostwriters: Enslaved Christians and the Making of the Bible.

London, William Collins, 2024.

Paperback 267 pages + back matter

In Public Library System.

From $52 online.

Reviewed by Ted Witham

The healing of the paralytic is a favourite story in the New Testament. We’ve heard the story. Four friends bring a paralysed man on a stretcher. Unable to carry the man through the crowd to Jesus, they lift the stretcher onto the roof and dig their way down to Jesus.

Except that the story nowhere calls the stretcher-bearers ‘friends’. In the Greek text, they are just called ‘they’ with no indication of their relationship with the man on the stretcher. Some details, however, point to the man’s identity. It took four men to carry him, and the stretcher itself was solid enough to be lowered through the roof. It was a substantial litter. This man is likely an enslaver, and his four bearers are enslaved.

If this is true, it twists the meaning of the story.

Enslaved people were not seen as people. And yet, when the stretcher touches down, Jesus addresses the four slaves. Courtesy demanded that he address the man being carried about, not his slaves. Jesus, however, chooses first to praise these slaves. He praises their loyalty, their faith. The Greek word pistis means both. In the story as we have it, these slaves come off well.

Only then does Jesus turn to the man on the mattress. He forgives his sin. Jesus faces down the scribes who accuse him of blasphemy. ‘No one can forgive sins but God alone.’ And then he tells the man, ‘Stand up, take up your mat and walk!’ It’s almost as though the man could do that all along. His ‘sin’ may have been ordering others to carry him about when there was no need. He was making that demand on them because, as a slave owner, he could.

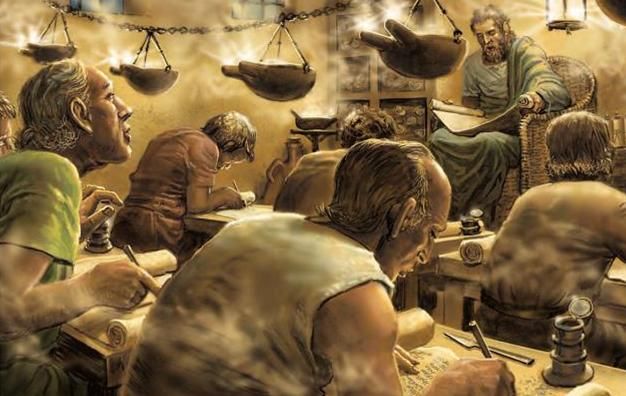

In God’s Ghostwriters, Candida Moss argues that enslaved people did much of the writing of the New Testament. Named authors like Paul depended on slaves well-trained in literacy to write down his words, edit them, and make copies of them. Messengers, who were usually slaves, would carry these words and read them, often as an after-dinner performance.

Professor Moss is Edward Cadbury Chair of Theology at the University of Birmingham. She is well-equipped to write about the ancient world and how the Christian scriptures fit into the Roman culture. She writes with verve and clarity.

Dr Moss argues that it is almost certain that these scribal tasks involved changing the words they were given.

Firstly, the slaves had to knead the master’s words into shape. This editing enabled those hearing the words to make sense of them.

Secondly, these slaves would have been tempted to make substantive changes to the text – and probably did. These tweaks would inevitably have introduced changes from the point of view of the enslaved, like the four stretcher-bearers digging through Peter’s roof being obedient slaves and not simply good-hearted friends.

Some parables, as Moss points out, make sense only from the enslaved point of view. Slaves, for example, would have been accustomed to absentee owners of vineyards who appointed their son as master of the vineyard. The slaves would see that one was the same as the other. So God and Jesus could be simultaneously distinct entities and one person.

Thirdly, as part of their task, messengers would be required to perform these stories or letters. It was the custom for these readings to use voice, gestures, props and other devices to hold the audience. At times when audience attention failed, they would tell the story in other more interesting words, even inventing new passages.

Candida Moss suggests that the ‘long ending’ of Mark’s Gospel may have come into existence in this way. The slave reading the text would come to the words at the end, ‘They said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid!’ In the atmosphere of a dinner at which wine had been consumed, diners would hear this as an anti-climax and the reader would be blamed. Why not add some stories of the appearances of Jesus, wild stories of handling snakes and drinking poison?

Professor Moss concludes that we cannot know the individual changes that enslaved people made in the development of the received texts of the Gospels and letters. But we can know for certain that slaves did do the writing and did make changes as they went.

After reading Professor Moss’s attractive book, I, for one, will not read the New Testament in the same spirit. I will now try to really see these enslaved writers,bring them out of the shadows where they have been taken for granted for 2,000 years, and see what new and fascinating truths God is teaching me through their work.

Noel Nannup OAM and Francesca Robertson,

Noel Nannup OAM and Francesca Robertson,